by Autumn Hilden

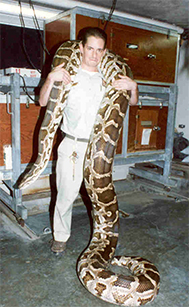

Curator of Reptiles, Amphibians and Fish Ian Recchio grew up around snakes. “Both my father and my uncle were serious amateur herpetologists, and that’s what we did for fun. We took family vacations to Baja and the deserts, looking for snakes.” It was a family pastime that ultimately led to a 30-year career at the Zoo, culminating in his role as curator, which is coming to a close as he retires from the Zoo in August. But the path wasn’t always set in stone.

“As I started to kind of branch off and try to figure out what the heck I was going to do with myself, I gravitated toward art,” he recalls. In fact, he majored in art in college, and it was his creative skills that Zoo staff were first interested in. “I started off as a volunteer, airbrushing some of the exhibits and doing exhibit fabrication in the old reptile house. Then I got a job as a part-time keeper.”

Of course, he came in with all the practical reptile experience he’d gained through his family, “but I learned exponentially more when I started working at the Zoo. I hadn’t worked with cobras or mambas until I came here.” That was the early ‘90s. Recchio worked his way up slowly but surely, he says. “It was about volunteering, making relationships, working really hard, showing up on time, being nice to people, helpful, and genuinely trying to make things better.” And he wasn’t just trying to be a good employee. “I wanted to be a curator and develop a collection. That was my goal.”

The Legacy of the LAIR

Recchio was thrilled to be working at a professional zoo and immediately saw the potential to do more naturalistic exhibits. “I brought a lot of new ideas and some artistic background to spruce up the exhibits, and that was something that I was always very proud of,” he says, “but in hindsight, it was just scraping the surface. There was still a mentality within the community back then,” he explains. “Keep the snakes hot, give them a rock, a water dish, and some gravel, and they’re happy … but that’s just not where the science was going.”

And then we built the LAIR.

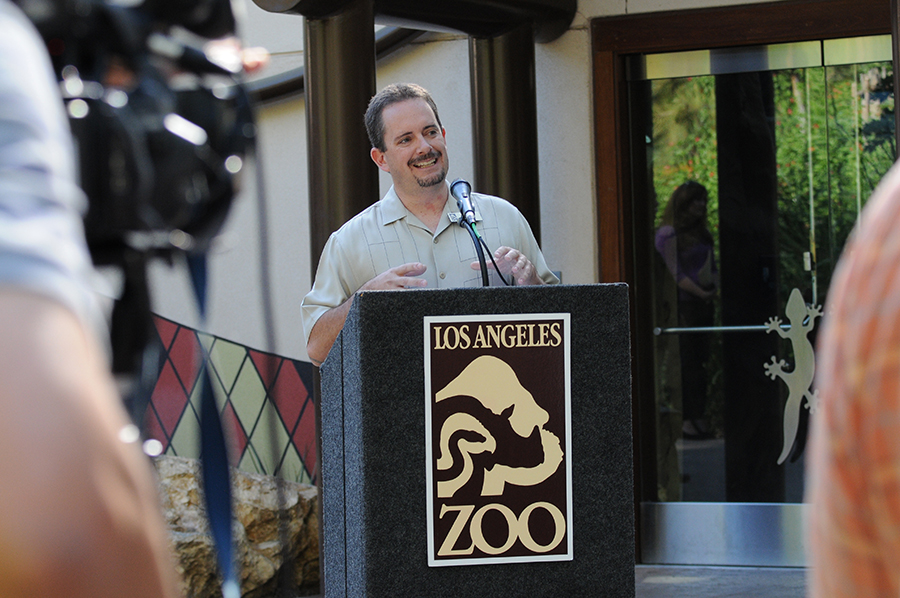

Dubbed “the LAIR” because the pair of buildings houses “Living Amphibians, Invertebrates, and Reptiles,” the Zoo’s new home for all things creepy and crawly opened up possibilities for creating mixed-species habitats and complete biomes for species that had been overlooked in the past. For Recchio, who became curator in 2007 and oversaw the LAIR opening in 2012, being able to develop a collection plan for a brand-new building was “golden,” he says. “The LAIR was such an upgrade. It was like going from a Pinto glass-back to a Ferrari.” A self-described “snake guy,” he made sure the LAIR has a little bit of everything. He describes it as, “a great crocodilian collection, a small but important tortoise and turtle collection, some really nice lizards and snakes, and a nice cross-section of amphibians, too.”

What he’s most proud of with the LAIR, though, is “just how beautiful the habitats are. With the mixed-species exhibits that are self-contained biomes—where we have living plants with frogs, and snakes, and fish—you finally get this bigger picture about the cycle of life,” he says. “People can understand the relationship between the habitat, people, and animals and that what they do—even the smallest things—can be helpful.”

Farther Afield

The LAIR provided a home base that Recchio was always proud to return to, but much of his work as curator has been far reaching. From childhood trips and into his career with the Zoo, Mexico and its biodiversity remain close to Recchio’s heart. He’s quick to note that Mexico has more species of reptile than any country on Earth.

“It made a lot of sense to have a robust collection of Mexican species in Los Angeles, because there’s a large population of Latin American people here that come from all different states in Mexico and Central America,” he says. “I see it all the time, I hear people saying in Spanish, ‘I remember seeing those in Durango when we were visiting the family,’ or ‘We used to have these cascabel in San Luis Potosi.’ Walking through the LAIR, you see species from this region that a lot of zoos don’t have.”

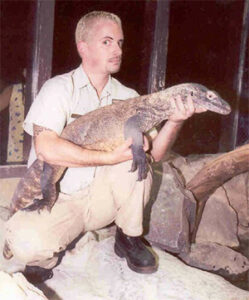

He’s also been on the Komodo dragon Species Survival Plan (SSP) steering committee for 15 years, contributing time and resources toward breeding this endangered species and moving the resulting offspring all over the world. In fact, more than 100 Komodos have come in and out of the Zoo on their way to safe destinations in Singapore, India, Europe, and Australia over the years of his tenure. “That’s a program that I’m super proud to have been a huge part of, both individually and as a team manager here,” he says. “That’s a big one.”

And then there are the animals that show up, unplanned, from far-off places. As Los Angeles is unfortunately a hub for illegal wildlife trafficking, Recchio estimates he’s seen hundreds of specimens that have been confiscated at the port. “Some of them we’ve been able to give a home here at the Zoo, but 90 percent have had to be moved to other facilities to hold, whether it be a university or another AZA zoo,” he explains. “One of the things that I am super proud of is being able to place animals that were dropped in our lap unexpectedly.” It takes a longtime expert in the field with extensive connections to be able to quickly ID obscure species, know the best facility options to care for them, and make safe arrangements.

A Wild Memory

In addition to all the animal care and serious science, there have been plenty of shocks and laughs for Recchio along the way. “Catching Reggie was just the craziest, most serendipitous thing ever,” he says immediately when asked about favorite memories during his tenure. The Zoo’s American alligator, Reggie, had “been loose for years,” before he was bought here. Kept illegally by a private owner who dropped him in Lake Machado when he could no longer handle his care, Reggie was a local legend. “Steve Irwin, the Crocodile Hunter, was supposed to come out and bring his staff to catch Reggie,” Recchio recalls. After Irwin’s untimely death, “Steve’s staff was going to honor his promise” and planned to still come out from Australia for the capture.

Recchio was in a downtown meeting about the Los Angeles Zoo’s preparations to take Reggie once he was caught. “I was in that meeting about it [when we got news that] Reggie showed up on the beach a few days before the crew was taking a Qantas airlines flight to help catch him. I ended up jumping up, recruiting a couple guys on the scene from Recreation and Parks—and we just got together and pulled him out of the mud!”

Lasting Connections

Maybe the moment with Reggie had a lasting effect on someone who’s “always been a pit viper guy.” When it comes to individual animals, he says, it’s “definitely the big crocodiles and the big Komodo,” he says of the links he feels with the LAIR species. He doesn’t call it a bond. “They’re smarter,” he clarifies. “There’s some intelligence there and a connection. They may look like they’re lying there like a log and staring through you without any thought, but they’re calculating, intelligent creatures, and you really get to know that after a while.”

Part of Recchio’s legacy at the Zoo has been fostering that connection for visitors, work that he has taken very seriously. “Let’s not sugarcoat it: there’s not a lot of wild left, period. It’s tough out there,” he says. “What we provide in professional, accredited zoos has a lot of value towards conservation. The southern mountain yellow-legged frog is one of our gold star conservation programs, because, in all likelihood, without the Los Angeles Zoo and its conservation partners they would eventually just be a picture in a textbook.” The L.A. Times even dubbed him a “rock star” for that work.

But it takes people to do the work, and not just professionals. “The large majority of our visitors walk through that LAIR and they see stuff that they’ve only heard of on TV or on the internet. Being able to educate people with real facts and having them nose to nose with a green mamba has a lot of value. The zoo is about animals and people.”

Recchio says he feels “really good” about handing off the baton to a new curator. While he’s been at the Zoo, he’s “tried to do hard things,” he says. “Some species we had, had never successfully reproduced, or we had never tried to breed them before, and I had many significant successes. The butaan (aka Gray’s monitor), for instance,” he says enthusiastically. He’s made great strides administratively as well, and he knows the value of his legacy. “The staff are in good shape, and we have a really sought-after collection and a beautiful facility.”

But there’s one thing he says he’ll think about when he’s gone. “One of my favorite things to do, before the public comes in and things are very quiet, is walking around and looking at the animals in the morning. I come in and walk through the animals and just quietly watch them. That that’s the one simple thing I love doing to this day. That’s what I’m going to miss the most.”