by Autumn Hilden

The Mating Game

The usual approach to pairing condors for breeding was to get them in the cage together as early as possible so they had the longest amount of time to get used to each other before breeding season. “When you put birds together in the non-breeding season, they really have no reason to be interested in each other,” Mike explains. “They’re competing for perches, food, the attention of birds next door. It can actually generate animosity.”

Mike discovered an opposite approach was even more effective. It started with the need to re-pair two males. The issue arose late in the season, so the option of long-lead introductions was not possible when two new females arrived at the Zoo. He had an idea.

“There’s no bigger turn-on to a male condor than a confident female, especially during breeding season,” Mike explains. So they removed the males from their habitats and placed the females there instead, allowing them to take ownership of the spaces. After a month, things started to gel.

“So the females start to show territoriality over their space,” says Mike. “You can tell by their posture and the way they’re walking around. The other birds are displaying or breeding next door, and you see by the females’ response to neighboring condors that they’re ready to be introduced to a new character in their own living space.” At that stage, the males were quietly placed into what’s called a “howdy” area, where the males and females can see each other but can’t interact.

“And we wait for the females to approach with the right posture: inflated neck, standing tall. The males are full of testosterone because of the time of year. And that’s his old stomping ground. And here’s this confident female in there,” he recounts. When the females approached the males in this state—“territorial but interested because the males are not so bad lookin’”—Mike gently and remotely raised the barrier between them. Within a single minute, the birds were engaging in behaviors of bonded pairs: walking together, going into nest boxes together (aka “house hunting”), displaying in the nest box, and even mounting. “It was 16 days from introduction to copulation. We had a fertile egg at 32 days and a live chick by 89 days. This is unprecedented in condor breeding,” Mike says. “Something that can take years to accomplish we were accomplishing in just a few weeks.

“It was something that we were planning to do, that we thought we could do.” But it took an unusual circumstance to allow them to test their theory. The new introduction process can establish a relationship in weeks and with higher levels of success. “I call it the Hail Mary,” he says, because the first time it succeeded was with pairs being introduced so late in the season. “We couldn’t be happier.”

A Certain Type of Person

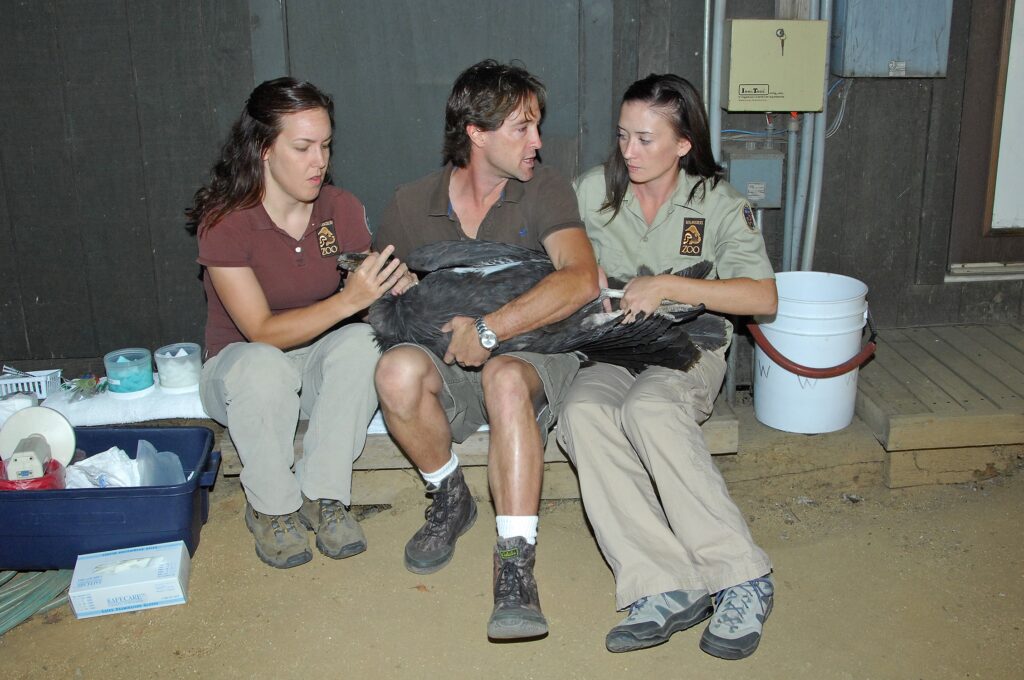

At this point, Mike and Chandra and their team of Debbie Sears, former keeper Jenny Williams, and newcomer Rhiann Ogata have built an entire innovative breeding program on their shared passion. “We trust so strongly in each other’s opinions and work, and it has just felt good to know that we have each other’s backs,” Chandra says.

One thing that the work has never been is boring. “It’s like a wheel of fortune,” Mike says. “Every day is different. I don’t even know what the word boring means.” “No, I’m never bored,” Chandra agrees. “And the cool thing—why it’s so addictive—is because you’re working with a species in your own backyard instead of having to fly to Costa Rica or into Africa.”

“Like anybody that does any in-depth work with condors, if you don’t get the bug you’re a different kind of human being,” Mike says.

“There’s a weird panic at the end of this career. This is my identity,” Chandra says.

Mike agrees it doesn’t feel quite right. “I’m here every day feeling like I just started this job. I’m still thinking about it! I’m still thinking of new stuff!”

Part of being successful has meant being all-in, all the time. “If you’re just coming here as your day job for eight hours and leaving, you cannot do the job,” Chandra says. “You can do the basic stuff, but you can’t do the long-term thinking. It really takes a certain type of person. And it is a long game.”

Over the years the job’s rigors have also presented physical challenges. In addition to work with eggs and birds on site at the Zoo, Mike and Chandra have participated in field work to retrieve extra eggs from remote nests in the wild. These nest entries are often perilous, requiring helicopter landings, long hikes, steep rappels, and one-armed returns with eggs or birds in hand.

“Now that we’re older it’s like, ‘I’m gonna get you some Advil,’ Chandra quips. Mike nods. “You’re working with field biologists that do this all day, and they’re in their 20s and eating popcorn and donuts for lunch, but you’ve got to keep up,” he says.