by Autumn Hilden

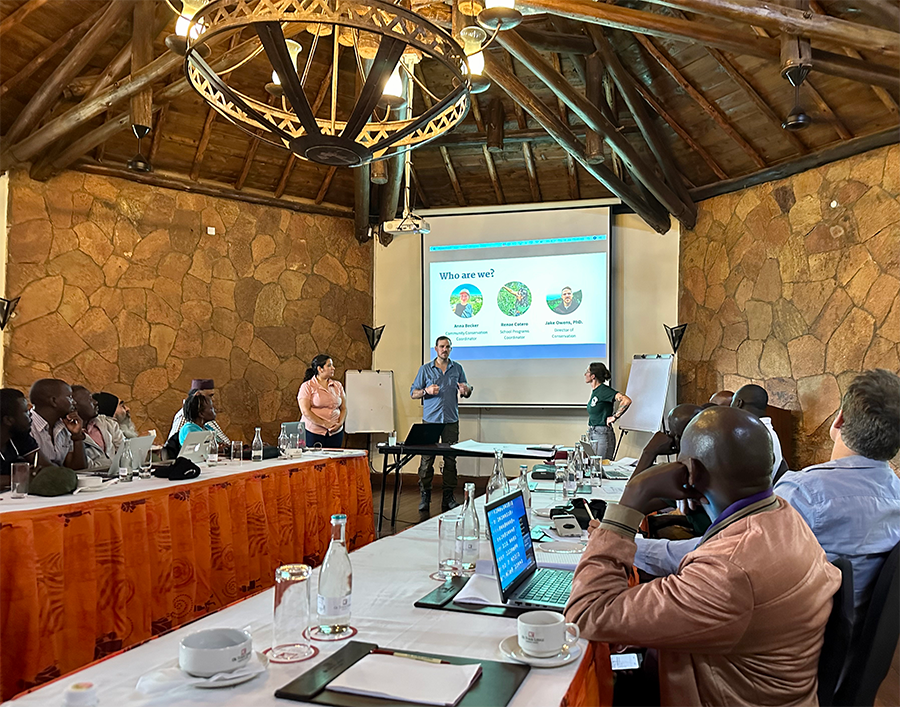

In 2021, the L.A. Zoo began discussing a partnership with the African Conservation Centre (ACC), an organization widely recognized for its successes in community-based conservation in Kenya. Dr. Jake Owens and Anna Becker from the Zoo’s Conservation Division and Renae Cotero from the Learning & Engagement Division recently traveled to Kenya as part of the Mark and Diane Montgomery Conservation Fellowship program to meet with partners from ACC to discuss a first-of-its-kind project in Africa.

The primary focus of the ACC and L.A. Zoo partnership is to develop the Noonkotiak Resource Centre near Amboseli National Park in Kenya. This center will be a knowledge-sharing hub that focuses on Amboseli ecosystem research, Maasai cultural experiences led by women, and educational resources for both local and international students.

During the 11-day trip, the Zoo team traveled from Nairobi to Amboseli National Park, the Chyulu Hills, and finally Laikipia County to conduct site visits, meet with partners, and participate in stakeholder conversations about the development and planning of the Noonkotiak Resource Centre.

“This is a Centre for this community, for these people,” says Owens. “We want to support them and the things that they’re trying to achieve, the goals and dreams and desires that they have. We’re here to help see it through so it succeeds for the intended purposes that they have.”

Luckily, they’re not starting from scratch but boosting efforts that are already in progress. In fact, the idea for the growth of the Centre has been in development for about ten years, Owens says. “One of the things that was brought up multiple times is that the L.A. Zoo coming in is bringing an excitement and enthusiasm for the project as a whole, to feel like it’s actually moving forward, finally.”

Cotero elaborates on the importance of being there. “To meet with the people and actually see and hear from them the things that they’re looking for, and the ways that the L.A. Zoo can help, it was nice to be felt as ‘being there,’” she says. Becker agrees. “We know that we’re committed to this project, and we know that we have huge expectations that we’re hoping to accomplish, but being able to show up and have that be something that they can start to see and realize is so important.”

The approach to collaboration is key when working with partners who’ve so often been minimized when it comes to their own land and practices. Historically, “local people have too often suffered at the expense of conservation,” Owens explains. He describes a common scenario in national parks around the globe, practiced from the early days of conservation work up through the recent past, where people who had worked the lands and had lived side by side with wildlife—for thousands of years in some cases—were forced out in the name of saving species.

But Amboseli National Park has had a long history of engagement with local communities; it’s one of the main reasons the Zoo sought to join the project in the first place. As part of the formation of Amboseli, African Conservation Center (ACC) chairman Dr. David Jonah Western pioneered conservation efforts that included local communities instead of displacing them, making him “an absolute living legend in conservation,” for Owens. The partnership approach created the “ethos” of the park, Owens says. “This project is to create a Centre that also demonstrates those ideas,” he shares. “It’s ultimately rooted in the idea that the people who live there are a central part of the ecosystem. The project itself supports people and their role in the ecosystem as a way to conserve the incredible biodiversity that is there.” It all works together in a circle of mutual benefit. “We’ve got social and environmental justice on our focal areas of the Zoo’s Conservation Strategic Plan, not just because we want to help people,” says Owens, “but because helping people and engaging with them in intentional ways supports biodiversity.”

Still, it takes a lot to build trust: face-to face meetings, demonstration of respect, and an ebb and flow of ideas and influence are all key. Becker heard firsthand of how trust had been broken in the past. “They shared examples of other groups that have come in, asked for meetings with them, sat down under the tree (the traditional meeting space), and promised them money for things, and then they never saw them again,” she says. “I’m excited, because I know we are committed and that we are trustworthy partners, to prove that to them. To build a strong and trustworthy, meaningful partnership: that is something that is expected when you work with us. They’re wonderful people, and they have this amazing space and knowledge, and that kind of partnership should be something that they get to demand.”

Embodying the ethos of respect that the Park was built on meant meeting local leaders on their terms. “Normally, you’d have your pretty presentation slides up, and you go through your slides and somebody’s talking,” explains Owens. “But when we met with the Maasai landowners and the people who are most directly going to benefit from the Noonkotiak Centre, we sat outside underneath the acacia tree. That’s a very common, comfortable, familiar way for them to engage.” In Kenya, acacia trees symbolize regeneration, perseverance, and integrity. They’re a place for important meetings, sharing of information, and remembrance of significant history.

“So we sat there under the tree, held up some printouts of the designs and talked, and then walked through the Noonkotiak Centre site with stakes and ropes, demonstrating the locations and sizes of various buildings. Afterwards we had a lunch together of big slabs of traditionally cooked goat meat under more acacia trees,” he says. It was a way for the Zoo group to signal respect and deference to the local customs.

Cotero could see the potential for mutual influence right away. “Working with the education team over there, it’s really inspiring to see the work that they’re already doing,” she says. “We can help supplement that, we can partner—and potentially bring ideas back here to the L.A. Zoo to do with our students. It’s inspiring to help the Kenyan people—and to learn from them.” It’s not about coming in with pre-packaged solutions that disregard the local expertise. Instead, “We’re finding ways we can collaborate,” she emphasizes.

And there is a lot of work to do. The Noonkotiak Centre will facilitate the advancement of community livelihoods, sustainable resource management, and human-wildlife coexistence by integrating research, policy, educational opportunities/knowledge sharing, and income-generating community projects and nature-based enterprises, including visitation from tourists. It will also conserve biodiversity and improve livelihoods in the Amboseli Ecosystem and beyond by applying traditional Maasai information-sharing practices and engagement of local and international communities. It’s being designed in three parts:

- Environmental Education and Visitor Centre – This Centre will communicate the ecological and social significance of the Amboseli Ecosystem to visitors. Long-term research will be housed here, and the Centre will also offer workshops and programs to school groups from the Amboseli Ecosystem and to other groups, including international visitors. It will also offer field excursions in and around Amboseli National Park. And, the Centre will include a library, a digital library, wildlife exhibits, cultural information, and a botanic garden.

- Research Monitoring and Knowledge-Sharing Centre – This Centre will be a place for local, national, and international researchers and students to conduct research on diverse ecological and sociological thematic areas to inform sound policies. Permanent, onsite, comfortable housing will be available for a limited number of researchers. The Centre will also provide research internships and scholarships for local youth to engage with scientists.

- Maasai Women’s Cultural Tourism Centre: Maasai Homestays – This Centre will provide visitors with an experiential learning opportunity that integrates wildlife viewing with the Maasai way of life. Sixteen cultural manyattas (small, unused settlements) will soon be upgraded for housing guests.

“The other thing that we’re particularly focusing on for the project is evaluation,” Owens says. “We want to evaluate what we’re doing now—the different aspects of the physical space, but also the programs that come out of it—to ensure that they actually meet the predefined objectives and goals. And we want to do that with good study design so it can be published and then help inform other people who are trying to do similar types of projects.” It’s a value informed by another area of focus for the Zoo’s Conservation Strategic Plan, evidence-based conservation, which demands scientifically supported conservation action.

Gathering evidence requires being there, soaking in the experiences, meeting the people, seeing the issues, and imagining the solutions together. The effect of an in-person visit like this one cannot be overstated, and, many times, it’s the personal connections that drive the hard project work for years to come.

“I think for me, the most impactful part was our visit at the Women’s Cultural Center in Twala,” says Cotero, reflecting on what about the trip is going to stay with her on a human level. “We were doing a medicinal plant walk tour, and the guide, she just kept hugging me and sharing everything. She’d take a bite out of a plant and then she’d hand it to me to eat the plant. Or we have pictures of us brushing our teeth together with traditional stick brushes. And then Rosemary, the woman who leads the program, told me of our guide, ‘She says you remind her of her daughter.’ And even though we were ‘tourists,’ they didn’t treat us like it. They wanted to show us their culture and their community. And they welcomed us with open arms…it makes you want to really do your best for them.”

Becker also was deeply moved by the women at Twala. “They were telling us stories about the barriers they’ve overcome as women,” she remembers. “I felt really honored to be able to hear and for them to share, because it wasn’t insignificant things that they were sharing. It was very personal. It was very culturally personal. I got really emotional,” she admits. “There’s cultural differences, sure, but also things that are really similar, things that we’re all working to gain as women.” She describes a “magic to it” that she hopes is something that they’re able to recreate in the Maasai Women’s Cultural Tourism Centre with the Maasai homestays at Noonkotiak Centre. “I hope whenever people visit, they fall in love with the people that are there. And vice versa. That love and kindness and support should be something that we’re working toward, not just in conservation, but as people.”

Owens was particularly inspired by time spent with some of his conservation heroes. “It was really an incredible experience to spend so much time with Dr. Jonah Western,” Owens says. “And his wife is Dr. Shirley Strum, who did the original behavioral work on baboons that I referenced heavily in my PhD. She’s a legend in the field for me.” The group went on a game drive through Amboseli with Western, then had dinner and talked about the Noonkotiak project with Strum, who helped start the Twala women’s community. “Conservation has historically traditionally focused on the animals and wildlife. But conservation challenges are rooted in human challenges, almost always,” he says. These giants in the field not only understand that truth, Jonah’s conservation work “from a very early time, was focusing on how to address human challenges and how to incorporate the things that people who have lived on those lands for a very long time were already doing really well: maintaining wildlife.”

Now the L.A. Zoo is playing a role in honoring and magnifying those efforts. We look forward to bringing you more stories from Amboseli as this important work continues.